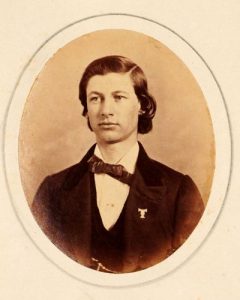

Francis Fentress, esq. (Bolivar, Tennessee). University of Mississippi 1861 Classbook. Courtesy of the University of Mississippi Department of Archives and Special Collections.

On February 22, 1861, Phi Sigma, one of two antebellum literary societies at the University of Mississippi, held its weekly meeting to facilitate an academic debate and conduct regular society business. During the meeting, however, Francis Fentress, a Phi Sigma member and University of Mississippi student from Bolivar, Tennessee, insisted that there were more pressing matters at hand. He introduced a motion to burn two abolitionist books held in the society’s library.

In calling for the destruction of these abolitionist books, Fentress was not only acting upon an abstract proslavery ideology, he was also working to protect his own very concrete interests in the institution: Fentress hailed from a slaveholding family and no doubt expected to become a slaveholder in his own right one day. In 1860, the federal census slave schedules revealed that, back in Tennessee, Fentress’s mother, Matilda, laid claim to eleven men, women, and children,1 while his brother James held nine.2 In Texas, meanwhile, his brother David also claimed nine enslaved people.3 Fentress continued to act in tangible ways to defend slavery in the months that followed. Shortly after graduating from the University of Mississippi, he joined the Confederate Army’s Seventh Tennessee Cavalry, ultimately rising to the rank of sergeant.4

Fentress’s investment in and commitment to slavery, made manifest in his motion, was broadly shared among members of Phi Sigma. The motion carried, and the society organized a special committee to oversee the destruction of these monographs.5 Because the society hired enslaved men to prepare and clean their meeting room, and specifically tasked these individuals with building fires, however, it is likely that an enslaved man, rather than the students who sought to keep him and other black people in bondage, built the fire used to burn the society’s abolitionist books.6

Notes:

1 U.S. Census Office, Eighth Census, 1860, Slave Schedules, Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee, s.v. “M.C. Fentress,” Ancestry Library, AncestryLibrary.com.

2 U.S. Census Office, Eighth Census, 1860, Slave Schedules, Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee, s.v. “Jomes Fentress,” Ancestry Library, AncestryLibrary.com.

3 U.S. Census Office, Eighth Census, 1860, Slave Schedules, Hays County, Texas, s.v. “M.W. Fentress,” Ancestry Library, AncestryLibrary.com. Note that in this entry the “D.” has been transcribed by Ancestry Library as “M.” The neighbors of D.W. Fentress in the regular census, the Brown family, appear as neighbors in the slave schedule.

4 John Allison, ed. Notable Men of Tennessee: Personal and Genealogical, with Portraits, vol. 2, (Atlanta: Southern Historical Association, 1905), 103.

5 Phi Sigma Debate Society Meeting Minutes. February 22, 1861. The Department of Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi.

6 Phi Sigma outlined the duties of the hired slave, including building fires, in their September 29, 1849 meeting.

By Andrew Marion and Anne Twitty | April 25, 2018